2.5 AL QAEDA'S RENEWAL IN AFGHANISTAN (1996-1998)

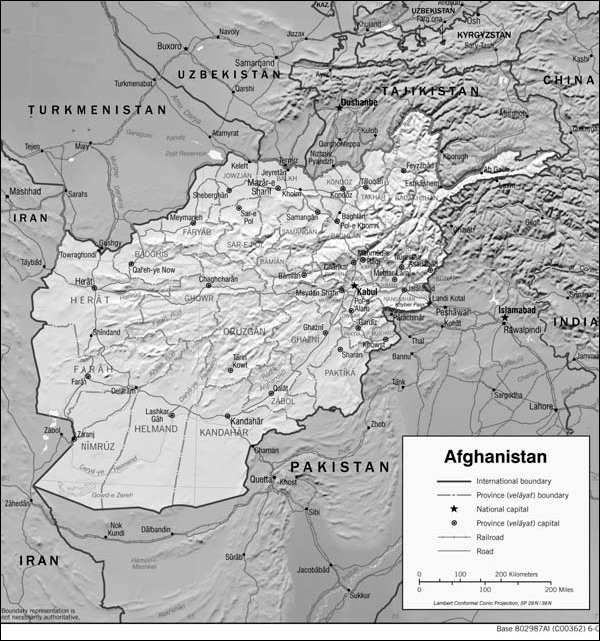

Bin Ladin flew on a leased aircraft from Khartoum to Jalalabad, with a refueling stopover in the United Arab Emirates.62 He was accompanied by family members and bodyguards, as well as by al Qaeda members who had been close associates since his organization's 1988 founding in Afghanistan. Dozens of additional militants arrived on later flights.63

Though Bin Ladin's destination was Afghanistan, Pakistan was the nation that held the key to his ability to use Afghanistan as a base from which to revive his ambitious enterprise for war against the United States.

For the first quarter century of its existence as a nation, Pakistan's identity had derived from Islam, but its politics had been decidedly secular. The army was--and remains--the country's strongest and most respected institution, and the army had been and continues to be preoccupied with its rivalry with India, especially over the disputed territory of Kashmir.

From the 1970s onward, religion had become an increasingly powerful force in Pakistani politics. After a coup in 1977, military leaders turned to Islamist groups for support, and fundamentalists became more prominent. South Asia had an indigenous form of Islamic fundamentalism, which had developed in the nineteenth century at a school in the Indian village of Deoband.64 The influence of the Wahhabi school of Islam had also grown, nurtured by Saudi-funded institutions. Moreover, the fighting in Afghanistan made Pakistan home to an enormous--and generally unwelcome--population of Afghan refugees; and since the badly strained Pakistani education system could not accommodate the refugees, the government increasingly let privately funded religious schools serve as a cost-free alternative. Over time, these schools produced large numbers of half-educated young men with no marketable skills but with deeply held Islamic views.65

Pakistan's rulers found these multitudes of ardent young Afghans a source of potential trouble at home but potentially useful abroad. Those who joined the Taliban movement, espousing a ruthless version of Islamic law, perhaps could bring order in chaotic Afghanistan and make it a cooperative ally. They thus might give Pakistan greater security on one of the several borders where Pakistani military officers hoped for what they called "strategic depth."66

It is unlikely that Bin Ladin could have returned to Afghanistan had Pakistan disapproved. The Pakistani military intelligence service probably had advance knowledge of his coming, and its officers may have facilitated his travel. During his entire time in Sudan, he had maintained guesthouses and training camps in Pakistan and Afghanistan. These were part of a larger network used by diverse organizations for recruiting and training fighters for Islamic insurgencies in such places as Tajikistan, Kashmir, and Chechnya. Pakistani intelligence officers reportedly introduced Bin Ladin to Taliban leaders in Kandahar, their main base of power, to aid his reassertion of control over camps near Khowst, out of an apparent hope that he would now expand the camps and make them available for training Kashmiri militants.67

Yet Bin Ladin was in his weakest position since his early days in the war against the Soviet Union. The Sudanese government had canceled the registration of the main business enterprises he had set up there and then put some of them up for public sale. According to a senior al Qaeda detainee, the government of Sudan seized everything Bin Ladin had possessed there.68

He also lost the head of his military committee, Abu Ubaidah al Banshiri, one of the most capable and popular leaders of al Qaeda. While most of the group's key figures had accompanied Bin Ladin to Afghanistan, Banshiri had remained in Kenya to oversee the training and weapons shipments of the cell set up some four years earlier. He died in a ferryboat accident on Lake Victoria just a few days after Bin Ladin arrived in Jalalabad, leaving Bin Ladin with a need to replace him not only in the Shura but also as supervisor of the cells and prospective operations in East Africa.69 He had to make other adjustments as well, for some al Qaeda members viewed Bin Ladin's return to Afghanistan as occasion to go off in their own directions. Some maintained collaborative relationships with al Qaeda, but many disengaged entirely.70

For a time, it may not have been clear to Bin Ladin that the Taliban would be his best bet as an ally. When he arrived in Afghanistan, they controlled much of the country, but key centers, including Kabul, were still held by rival warlords. Bin Ladin went initially to Jalalabad, probably because it was in an area controlled by a provincial council of Islamic leaders who were not major contenders for national power. He found lodgings with Younis Khalis, the head of one of the main mujahideen factions. Bin Ladin apparently kept his options open, maintaining contacts with Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who, though an Islamic extremist, was also one of the Taliban's most militant opponents. But after September 1996, when first Jalalabad and then Kabul fell to the Taliban, Bin Ladin cemented his ties with them.71

That process did not always go smoothly. Bin Ladin, no longer constrained by the Sudanese, clearly thought that he had new freedom to publish his appeals for jihad. At about the time when the Taliban were making their final drive toward Jalalabad and Kabul, Bin Ladin issued his August 1996 fatwa, saying that "We... have been prevented from addressing the Muslims," but expressing relief that "by the grace of Allah, a safe base here is now available in the high Hindu Kush mountains in Khurasan." But the Taliban, like the Sudanese, would eventually hear warnings, including from the Saudi monarchy.72

Though Bin Ladin had promised Taliban leaders that he would be circumspect, he broke this promise almost immediately, giving an inflammatory interview to CNN in March 1997. The Taliban leader Mullah Omar promptly "invited" Bin Ladin to move to Kandahar, ostensibly in the interests of Bin Ladin's own security but more likely to situate him where he might be easier to control.73

There is also evidence that around this time Bin Ladin sent out a number of feelers to the Iraqi regime, offering some cooperation. None are reported to have received a significant response. According to one report, Saddam Hussein's efforts at this time to rebuild relations with the Saudis and other Middle Eastern regimes led him to stay clear of Bin Ladin.74

In mid-1998, the situation reversed; it was Iraq that reportedly took the initiative. In March 1998, after Bin Ladin's public fatwa against the United States, two al Qaeda members reportedly went to Iraq to meet with Iraqi intelligence. In July, an Iraqi delegation traveled to Afghanistan to meet first with the Taliban and then with Bin Ladin. Sources reported that one, or perhaps both, of these meetings was apparently arranged through Bin Ladin's Egyptian deputy, Zawahiri, who had ties of his own to the Iraqis. In 1998, Iraq was under intensifying U.S. pressure, which culminated in a series of large air attacks in December.75

Similar meetings between Iraqi officials and Bin Ladin or his aides may have occurred in 1999 during a period of some reported strains with the Taliban. According to the reporting, Iraqi officials offered Bin Ladin a safe haven in Iraq. Bin Ladin declined, apparently judging that his circumstances in Afghanistan remained more favorable than the Iraqi alternative. The reports describe friendly contacts and indicate some common themes in both sides' hatred of the United States. But to date we have seen no evidence that these or the earlier contacts ever developed into a collaborative operational relationship. Nor have we seen evidence indicating that Iraq cooperated with al Qaeda in developing or carrying out any attacks against the United States.76

Bin Ladin eventually enjoyed a strong financial position in Afghanistan, thanks to Saudi and other financiers associated with the Golden Chain. Through his relationship with Mullah Omar--and the monetary and other benefits that it brought the Taliban--Bin Ladin was able to circumvent restrictions; Mullah Omar would stand by him even when other Taliban leaders raised objections. Bin Ladin appeared to have in Afghanistan a freedom of movement that he had lacked in Sudan. Al Qaeda members could travel freely within the country, enter and exit it without visas or any immigration procedures, purchase and import vehicles and weapons, and enjoy the use of official Afghan Ministry of Defense license plates. Al Qaeda also used the Afghan state-owned Ariana Airlines to courier money into the country.77

The Taliban seemed to open the doors to all who wanted to come to Afghanistan to train in the camps. The alliance with the Taliban provided al Qaeda a sanctuary in which to train and indoctrinate fighters and terrorists, import weapons, forge ties with other jihad groups and leaders, and plot and staff terrorist schemes. While Bin Ladin maintained his own al Qaeda guesthouses and camps for vetting and training recruits, he also provided support to and benefited from the broad infrastructure of such facilities in Afghanistan made available to the global network of Islamist movements. U.S. intelligence estimates put the total number of fighters who underwent instruction in Bin Ladin-supported camps in Afghanistan from 1996 through 9/11 at 10, 000 to 20, 000.78

In addition to training fighters and special operators, this larger network of guesthouses and camps provided a mechanism by which al Qaeda could screen and vet candidates for induction into its own organization. Thousands flowed through the camps, but no more than a few hundred seem to have become al Qaeda members. From the time of its founding, al Qaeda had employed training and indoctrination to identify "worthy" candidates.79

Al Qaeda continued meanwhile to collaborate closely with the many Middle Eastern groups--in Egypt, Algeria, Yemen, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia, Somalia, and elsewhere--with which it had been linked when Bin Ladin was in Sudan. It also reinforced its London base and its other offices around Europe, the Balkans, and the Caucasus. Bin Ladin bolstered his links to extremists in South and Southeast Asia, including the Malaysian-Indonesian JI and several Pakistani groups engaged in the Kashmir conflict.80

The February 1998 fatwa thus seems to have been a kind of public launch of a renewed and stronger al Qaeda, after a year and a half of work. Having rebuilt his fund-raising network, Bin Ladin had again become the rich man of the jihad movement. He had maintained or restored many of his links with terrorists elsewhere in the world. And he had strengthened the internal ties in his own organization.

The inner core of al Qaeda continued to be a hierarchical top-down group with defined positions, tasks, and salaries. Most but not all in this core swore fealty (or bayat) to Bin Ladin. Other operatives were committed to Bin Ladin or to his goals and would take assignments for him, but they did not swear bayat and maintained, or tried to maintain, some autonomy. A looser circle of adherents might give money to al Qaeda or train in its camps but remained essentially independent. Nevertheless, they constituted a potential resource for al Qaeda.81

Now effectively merged with Zawahiri's Egyptian Islamic Jihad,82 al Qaeda promised to become the general headquarters for international terrorism, without the need for the Islamic Army Shura. Bin Ladin was prepared to pick up where he had left off in Sudan. He was ready to strike at "the head of the snake."

Al Qaeda's role in organizing terrorist operations had also changed. Before the move to Afghanistan, it had concentrated on providing funds, training, and weapons for actions carried out by members of allied groups. The attacks on the U.S. embassies in East Africa in the summer of 1998 would take a different form--planned, directed, and executed by al Qaeda, under the direct supervision of Bin Ladin and his chief aides.

The Embassy Bombings

As early as December 1993, a team of al Qaeda operatives had begun casing targets in Nairobi for future attacks. It was led by Ali Mohamed, a former Egyptian army officer who had moved to the United States in the mid-1980s, enlisted in the U.S. Army, and became an instructor at Fort Bragg. He had provided guidance and training to extremists at the Farouq mosque in Brooklyn, including some who were subsequently convicted in the February 1993 attack on the World Trade Center. The casing team also included a computer expert whose write-ups were reviewed by al Qaeda leaders.83

The team set up a makeshift laboratory for developing their surveillance photographs in an apartment in Nairobi where the various al Qaeda operatives and leaders based in or traveling to the Kenya cell sometimes met. Banshiri, al Qaeda's military committee chief, continued to be the operational commander of the cell; but because he was constantly on the move, Bin Ladin had dispatched another operative, Khaled al Fawwaz, to serve as the on-site manager. The technical surveillance and communications equipment employed for these casing missions included state-of-the-art video cameras obtained from China and from dealers in Germany. The casing team also reconnoitered targets in Djibouti.84

As early as January 1994, Bin Ladin received the surveillance reports, complete with diagrams prepared by the team's computer specialist. He, his top military committee members--Banshiri and his deputy, Abu Hafs al Masri (also known as Mohammed Atef)--and a number of other al Qaeda leaders reviewed the reports. Agreeing that the U.S. embassy in Nairobi was an easy target because a car bomb could be parked close by, they began to form a plan. Al Qaeda had begun developing the tactical expertise for such attacks months earlier, when some of its operatives--top military committee members and several operatives who were involved with the Kenya cell among them--were sent to Hezbollah training camps in Lebanon.85

The cell in Kenya experienced a series of disruptions that may in part account for the relatively long delay before the attack was actually carried out. The difficulties Bin Ladin began to encounter in Sudan in 1995, his move to Afghanistan in 1996, and the months spent establishing ties with the Taliban may also have played a role, as did Banshiri's accidental drowning.

In August 1997, the Kenya cell panicked. The London Daily Telegraph reported that Madani al Tayyib, formerly head of al Qaeda's finance committee, had turned himself over to the Saudi government. The article said (incorrectly) that the Saudis were sharing Tayyib's information with the U.S. and British authorities.86 At almost the same time, cell members learned that U.S. and Kenyan agents had searched the Kenya residence of Wadi al Hage, who had become the new on-site manager in Nairobi, and that Hage's telephone was being tapped. Hage was a U.S. citizen who had worked with Bin Ladin in Afghanistan in the 1980s, and in 1992 he went to Sudan to become one of al Qaeda's major financial operatives. When Hage returned to the United States to appear before a grand jury investigating Bin Ladin, the job of cell manager was taken over by Harun Fazul, a Kenyan citizen who had been in Bin Ladin's advance team to Sudan back in 1990. Harun faxed a report on the "security situation" to several sites, warning that "the crew members in East Africa is [sic] in grave danger" in part because "America knows... that the followers of [Bin Ladin]... carried out the operations to hit Americans in Somalia." The report provided instructions for avoiding further exposure.87

On February 23, 1998, Bin Ladin issued his public fatwa. The language had been in negotiation for some time, as part of the merger under way between Bin Ladin's organization and Zawahiri's Egyptian Islamic Jihad. Less than a month after the publication of the fatwa, the teams that were to carry out the embassy attacks were being pulled together in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. The timing and content of their instructions indicate that the decision to launch the attacks had been made by the time the fatwa was issued.88

The next four months were spent setting up the teams in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam. Members of the cells rented residences, and purchased bomb-making materials and transport vehicles. At least one additional explosives expert was brought in to assist in putting the weapons together. In Nairobi, a hotel room was rented to put up some of the operatives. The suicide trucks were purchased shortly before the attack date.89

While this was taking place, Bin Ladin continued to push his public message. On May 7, the deputy head of al Qaeda's military committee, Mohammed Atef, faxed to Bin Ladin's London office a new fatwa issued by a group of sheikhs located in Afghanistan. A week later, it appeared in Al Quds al Arabi, the same Arabic-language newspaper in London that had first published Bin Ladin's February fatwa, and it conveyed the same message--the duty of Muslims to carry out holy war against the enemies of Islam and to expel the Americans from the Gulf region. Two weeks after that, Bin Ladin gave a videotaped interview to ABC News with the same slogans, adding that "we do not differentiate between those dressed in military uniforms and civilians; they are all targets in this fatwa."90

By August 1, members of the cells not directly involved in the attacks had mostly departed from East Africa. The remaining operatives prepared and assembled the bombs, and acquired the delivery vehicles. On August 4, they made one last casing run at the embassy in Nairobi. By the evening of August 6, all but the delivery teams and one or two persons assigned to remove the evidence trail had left East Africa. Back in Afghanistan, Bin Ladin and the al Qaeda leadership had left Kandahar for the countryside, expecting U.S. retaliation. Declarations taking credit for the attacks had already been faxed to the joint al Qaeda-Egyptian Islamic Jihad office in Baku, with instructions to stand by for orders to "instantly" transmit them to Al Quds al Arabi. One proclaimed "the formation of the Islamic Army for the Liberation of the Holy Places," and two others--one for each embassy--announced that the attack had been carried out by a "company" of a "battalion" of this "Islamic Army."91

On the morning of August 7, the bomb-laden trucks drove into the embassies roughly five minutes apart--about 10:35 A. M. in Nairobi and 10:39 A.M. in Dar es Salaam. Shortly afterward, a phone call was placed from Baku to London. The previously prepared messages were then faxed to London.92

The attack on the U.S. embassy in Nairobi destroyed the embassy and killed 12 Americans and 201 others, almost all Kenyans. About 5, 000 people were injured. The attack on the U.S. embassy in Dar es Salaam killed 11 more people, none of them Americans. Interviewed later about the deaths of the Africans, Bin Ladin answered that "when it becomes apparent that it would be impossible to repel these Americans without assaulting them, even if this involved the killing of Muslims, this is permissible under Islam." Asked if he had indeed masterminded these bombings, Bin Ladin said that the World Islamic Front for jihad against "Jews and Crusaders" had issued a "crystal clear" fatwa. If the instigation for jihad against the Jews and the Americans to liberate the holy places "is considered a crime," he said, "let history be a witness that I am a criminal."93