7.3 ASSEMBLING THE TEAMS

During the summer and early autumn of 2000, Bin Ladin and senior al Qaeda leaders in Afghanistan started selecting the muscle hijackers--the operatives who would storm the cockpits and control the passengers. Despite the phrase widely used to describe them, the so-called muscle hijackers were not at all physically imposing; most were between 5' 5" and 5' 7" in height.83

Recruitment and Selection for 9/11

Twelve of the 13 muscle hijackers (excluding Nawaf al Hazmi and Mihdhar) came from Saudi Arabia: Satam al Suqami, Wail al Shehri, Waleed al Shehri, Abdul Aziz al Omari, Ahmed al Ghamdi, Hamza al Ghamdi, Mohand al Shehri, Majed Moqed, Salem al Hazmi, Saeed al Ghamdi, Ahmad al Haznawi, and Ahmed al Nami. The remaining recruit, Fayez Banihammad, came from the UAE. He appears to have played a unique role among the muscle hijackers because of his work with one of the plot's financial facilitators, Mustafa al Hawsawi.84

Saudi authorities interviewed the relatives of these men and have briefed us on what they found. The muscle hijackers came from a variety of educational and societal backgrounds. All were between 20 and 28 years old; most were unemployed with no more than a high school education and were unmarried.85

Four of them--Ahmed al Ghamdi, Saeed al Ghamdi, Hamza al Ghamdi, and Ahmad al Haznawi--came from a cluster of three towns in the al Bahah region, an isolated and underdeveloped area of Saudi Arabia, and shared the same tribal affiliation. None had a university degree. Their travel patterns and information from family members suggest that the four may have been in contact with each other as early as the fall of 1999.86

Five more--Wail al Shehri, Waleed al Shehri, Abdul Aziz al Omari, Mohand al Shehri, and Ahmed al Nami--came from Asir Province, a poor region in southwestern Saudi Arabia that borders Yemen; this weakly policed area is sometimes called "the wild frontier." Wail and Waleed al Shehri were brothers. All five in this group had begun university studies. Omari had graduated with honors from high school, had attained a degree from the Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University, was married, and had a daughter.87

The three remaining muscle hijackers from Saudi Arabia were Satam al Suqami, Majed Moqed, and Salem al Hazmi. Suqami came from Riyadh. Moqed hailed from a small town called Annakhil, west of Medina. Suqami had very little education, and Moqed had dropped out of university. Neither Suqami nor Moqed appears to have had ties to the other, or to any of the other operatives, before getting involved with extremists, probably by 1999.88

Salem al Hazmi, a younger brother of Nawaf, was born in Mecca. Salem's family recalled him as a quarrelsome teenager. His brother Nawaf probably recommended him for recruitment into al Qaeda. One al Qaeda member who knew them says that Nawaf pleaded with Bin Ladin to allow Salem to participate in the 9/11 operation.89

Detainees have offered varying reasons for the use of so many Saudi operatives. Binalshibh argues that al Qaeda wanted to send a message to the government of Saudi Arabia about its relationship with the United States. Several other al Qaeda figures, however, have stated that ethnicity generally was not a factor in the selection of operatives unless it was important for security or operational reasons.90

KSM, for instance, denies that Saudis were chosen for the 9/11 plot to drive a wedge between the United States and Saudi Arabia, and stresses practical reasons for considering ethnic background when selecting operatives. He says that so many were Saudi because Saudis comprised the largest portion of the pool of recruits in the al Qaeda training camps. KSM estimates that in any given camp, 70 percent of the mujahideen were Saudi, 20 percent wereYemeni, and 10 percent were from elsewhere. Although Saudi and Yemeni trainees were most often willing to volunteer for suicide operations, prior to 9/11 it was easier for Saudi operatives to get into the United States.91

Most of the Saudi muscle hijackers developed their ties to extremists two or three years before the attacks. Their families often did not consider these young men religious zealots. Some were perceived as devout, others as lacking in faith. For instance, although Ahmed al Ghamdi, Hamza al Ghamdi, and Saeed al Ghamdi attended prayer services regularly and Omari often served as an imam at his mosque in Saudi Arabia, Suqami and Salem al Hazmi appeared unconcerned with religion and, contrary to Islamic law, were known to drink alcohol.92

Like many other al Qaeda operatives, the Saudis who eventually became the muscle hijackers were targeted for recruitment outside Afghanistan-- probably in Saudi Arabia itself. Al Qaeda recruiters, certain clerics, and--in a few cases--family members probably all played a role in spotting potential candidates. Several of the muscle hijackers seem to have been recruited through contacts at local universities and mosques.93

According to the head of one of the training camps in Afghanistan, some were chosen by unnamed Saudi sheikhs who had contacts with al Qaeda. Omari, for example, is believed to have been a student of a radical Saudi cleric named Sulayman al Alwan. His mosque, which is located in al Qassim Province, is known among more moderate clerics as a "terrorist factory." The province is at the very heart of the strict Wahhabi movement in Saudi Arabia. Saeed al Ghamdi and Mohand al Shehri also spent time in al Qassim, both breaking with their families. According to his father, Mohand al Shehri's frequent visits to this area resulted in his failing exams at his university in Riyadh. Saeed al Ghamdi transferred to a university in al Qassim, but he soon stopped talking to his family and dropped out of school without informing them.94

The majority of these Saudi recruits began to break with their families in late 1999 and early 2000.According to relatives, some recruits began to make arrangements for extended absences. Others exhibited marked changes in behavior before disappearing. Salem al Hazmi's father recounted that Salem-- who had had problems with alcohol and petty theft--stopped drinking and started attending mosque regularly three months before he disappeared.95

Several family members remembered that their relatives had expressed a desire to participate in jihad, particularly in Chechnya. None had mentioned going to Afghanistan. These statements might be true or cover stories. The four recruits from the al Ghamdi tribe, for example, all told their families that they were going to Chechnya. Only two--Ahmed al Ghamdi and Saeed al Ghamdi--had documentation suggesting travel to a Russian republic.96

Some aspiring Saudi mujahideen, intending to go to Chechnya, encountered difficulties along the way and diverted to Afghanistan. In 1999, Ibn al Khattab--the primary commander of Arab nationals in Chechnya--reportedly had started turning away most foreign mujahideen because of their inexperience and inability to adjust to the local conditions. KSM states that several of the 9/11 muscle hijackers faced problems traveling to Chechnya and so went to Afghanistan, where they were drawn into al Qaeda.97

Khallad has offered a more detailed story of how such diversions occurred. According to him, a number of Saudi mujahideen who tried to go to Chechnya in 1999 to fight the Russians were stopped at the Turkish-Georgian border. Upon arriving in Turkey, they received phone calls at guesthouses in places such as Istanbul and Ankara, informing them that the route to Chechnya via Georgia had been closed. These Saudis then decided to travel to Afghanistan, where they could train and wait to make another attempt to enter Chechnya during the summer of 2000.While training at al Qaeda camps, a dozen of them heard Bin Ladin's speeches, volunteered to become suicide operatives, and eventually were selected as muscle hijackers for the planes operation. Khallad says he met a number of them at the Kandahar airport, where they were helping to provide extra security. He encouraged Bin Ladin to use them. Khallad claims to have been closest with Saeed al Ghamdi, whom he convinced to become a martyr and whom he asked to recruit a friend, Ahmed al Ghamdi, to the same cause. Although Khallad claims not to recall everyone from this group who was later chosen for the 9/11 operation, he says they also included Suqami, Waleed and Wail al Shehri, Omari, Nami, Hamza al Ghamdi, Salem al Hazmi, and Moqed.98

According to KSM, operatives volunteered for suicide operations and, for the most part, were not pressured to martyr themselves. Upon arriving in Afghanistan, a recruit would fill out an application with standard questions, such as, What brought you to Afghanistan? How did you travel here? How did you hear about us? What attracted you to the cause? What is your educational background? Where have you worked before? Applications were valuable for determining the potential of new arrivals, for filtering out potential spies from among them, and for identifying recruits with special skills. For instance, as pointed out earlier, Hani Hanjour noted his pilot training. Prospective operatives also were asked whether they were prepared to serve as suicide operatives; those who answered in the affirmative were interviewed by senior al Qaeda lieutenant Muhammad Atef.99

KSM claims that the most important quality for any al Qaeda operative was willingness to martyr himself. Khallad agrees, and claims that this criterion had preeminence in selecting the planes operation participants. The second most important criterion was demonstrable patience, Khallad says, because the planning for such attacks could take years.100

Khallad claims it did not matter whether the hijackers had fought in jihad previously, since he believes that U.S. authorities were not looking for such operatives before 9/11. But KSM asserts that young mujahideen with clean records were chosen to avoid raising alerts during travel. The al Qaeda training camp head mentioned above adds that operatives with no prior involvement in activities likely to be known to international security agencies were purposefully selected for the 9/11 attacks.101

Most of the muscle hijackers first underwent basic training similar to that given other al Qaeda recruits. This included training in firearms, heavy weapons, explosives, and topography. Recruits learned discipline and military life. They were subjected to artificial stresses to measure their psychological fitness and commitment to jihad. At least seven of the Saudi muscle hijackers took this basic training regime at the al Faruq camp near Kandahar. This particular camp appears to have been the preferred location for vetting and training the potential muscle hijackers because of its proximity to Bin Ladin and senior al Qaeda leadership. Two others--Suqami and Moqed--trained at Khaldan, another large basic training facility located near Kabul, where Mihdhar had trained in the mid-1990s.102

By the time operatives for the planes operation were picked in mid-2000, some of them had been training in Afghanistan for months, others were just arriving for the first time, and still others may have been returning after prior visits to the camps. According to KSM, Bin Ladin would travel to the camps to deliver lectures and meet the trainees personally. If Bin Ladin believed a trainee held promise for a special operation, that trainee would be invited to the al Qaeda leader's compound at Tarnak Farms for further meetings.103

KSM claims that Bin Ladin could assess new trainees very quickly, in about ten minutes, and that many of the 9/11 hijackers were selected in this manner. Bin Ladin, assisted by Atef, personally chose all the future muscle hijackers for the planes operation, primarily between the summer of 2000 and April 2001. Upon choosing a trainee, Bin Ladin would ask him to swear loyalty for a suicide operation. After the selection and oath-swearing, the operative would be sent to KSM for training and the filming of a martyrdom video, a function KSM supervised as head of al Qaeda's media committee.104

KSM sent the muscle hijacker recruits on to Saudi Arabia to obtain U.S. visas. He gave them money (about $2, 000 each) and instructed them to return to Afghanistan for more training after obtaining the visas. At this early stage, the operatives were not told details about the operation. The majority of the Saudi muscle hijackers obtained U.S. visas in Jeddah or Riyadh between September and November of 2000.105

KSM told potential hijackers to acquire new "clean" passports in their home countries before applying for a U.S. visa. This was to avoid raising suspicion about previous travel to countries where al Qaeda operated. Fourteen of the 19 hijackers, including nine Saudi muscle hijackers, obtained new passports. Some of these passports were then likely doctored by the al Qaeda passport division in Kandahar, which would add or erase entry and exit stamps to create "false trails" in the passports.106

In addition to the operatives who eventually participated in the 9/11 attacks as muscle hijackers, Bin Ladin apparently selected at least nine other Saudis who, for various reasons, did not end up taking part in the operation: Mohamed Mani Ahmad al Kahtani, Khalid Saeed Ahmad al Zahrani, Ali Abd al Rahman al Faqasi al Ghamdi, Saeed al Baluchi, Qutaybah al Najdi, Zuhair al Thubaiti, Saeed Abdullah Saeed al Ghamdi, Saud al Rashid, and Mushabib al Hamlan. A tenth individual, a Tunisian with Canadian citizenship named Abderraouf Jdey, may have been a candidate to participate in 9/11, or he may have been a candidate for a later attack. These candidate hijackers either backed out, had trouble obtaining needed travel documents, or were removed from the operation by the al Qaeda leadership. Khallad believes KSM wanted between four and six operatives per plane. KSM states that al Qaeda had originally planned to use 25 or 26 hijackers but ended up with only the 19.107

Final Training and Deployment to the United States

Having acquired U.S. visas in Saudi Arabia, the muscle hijackers returned to Afghanistan for special training in late 2000 to early 2001.The training reportedly was conducted at the al Matar complex by Abu Turab al Jordani, one of only a handful of al Qaeda operatives who, according to KSM, was aware of the full details of the planned planes operation. Abu Turab taught the operatives how to conduct hijackings, disarm air marshals, and handle explosives. He also trained them in bodybuilding and provided them with a few basic English words and phrases.108

According to KSM, Abu Turab even had the trainees butcher a sheep and a camel with a knife to prepare to use knives during the hijackings. The recruits learned to focus on storming the cockpit at the earliest opportunity when the doors first opened, and to worry about seizing control over the rest of the plane later. The operatives were taught about other kinds of attack as well, such as truck bombing, so that they would not be able to disclose the exact nature of their operation if they were caught. According to KSM, the muscle did not learn the full details--including the plan to hijack planes and fly them into buildings--before reaching the United States.109

After training in Afghanistan, the operatives went to a safehouse maintained by KSM in Karachi and stayed there temporarily before being deployed to the United States via the UAE.The safehouse was run by al Qaeda operative Abd al Rahim Ghulum Rabbani, also known as Abu Rahmah, a close associate of KSM who assisted him for three years by finding apartments and lending logistical support to operatives KSM would send.

According to an al Qaeda facilitator, operatives were brought to the safe-house by a trusted Pakistani al Qaeda courier named Abdullah Sindhi, who also worked for KSM. The future hijackers usually arrived in groups of two or three, staying at the safe house for as long as two weeks. The facilitator has identified each operative whom he assisted at KSM's direction in the spring of 2001. Before the operatives left Pakistan, each of them received $10, 000 from KSM for future expenses.110

From Pakistan, the operatives transited through the UAE en route to the United States. In the Emirates they were assisted primarily by al Qaeda operatives Ali Abdul Aziz Ali and Mustafa al Hawsawi. Ali apparently assisted nine future hijackers between April and June 2001 as they came through Dubai. He helped them with plane tickets, traveler's checks, and hotel reservations; he also taught them about everyday aspects of life in the West, such as purchasing clothes and ordering food. Dubai, a modern city with easy access to a major airport, travel agencies, hotels, and Western commercial establishments, was an ideal transit point.111

Ali reportedly assumed the operatives he was helping were involved in a big operation in the United States, he did not know the details.112 When he asked KSM to send him an assistant, KSM dispatched Hawsawi, who had worked on al Qaeda's media committee in Kandahar. Hawsawi helped send the last four operatives (other than Mihdhar) to the United States from the UAE. Hawsawi would consult with Atta about the hijackers' travel schedules to the United States and later check with Atta to confirm that each had arrived. Hawsawi told the muscle hijackers that they would be met by Atta at the airport. Hawsawi also facilitated some of the operation's financing.113

The muscle hijackers began arriving in the United States in late April 2001. In most cases, they traveled in pairs on tourist visas and entered the United States in Orlando or Miami, Florida; Washington, D.C.; or New York. Those arriving in Florida were assisted by Atta and Shehhi, while Hazmi and Hanjour took care of the rest. By the end of June, 14 of the 15 muscle hijackers had crossed the Atlantic.114

The muscle hijackers supplied an infusion of funds, which they carried as a mixture of cash and traveler's checks purchased in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Seven muscle hijackers are known to have purchased a total of nearly $50, 000 in traveler's checks that were used in the United States. Moreover, substantial deposits into operatives' U.S. bank accounts immediately followed the entry of other muscle hijackers, indicating that those newcomers brought money with them as well. In addition, muscle hijacker Banihammad came to the United States after opening bank accounts in the UAE into which were deposited the equivalent of approximately $30, 000 on June 25, 2001.After his June 27 arrival in the United States, Banihammad made Visa and ATM withdrawals from his UAE accounts.115

The hijackers made extensive use of banks in the United States, choosing both branches of major international banks and smaller regional banks. All of the hijackers opened accounts in their own name, and used passports and other identification documents that appeared valid on their face. Contrary to numerous published reports, there is no evidence the hijackers ever used false Social Security numbers to open any bank accounts. While the hijackers were not experts on the use of the U.S. financial system, nothing they did would have led the banks to suspect criminal behavior, let alone a terrorist plot to commit mass murder.116

The last muscle hijacker to arrive was Khalid al Mihdhar. As mentioned earlier, he had abandoned Hazmi in San Diego in June 2000 and returned to his family in Yemen. Mihdhar reportedly stayed in Yemen for about a month before Khallad persuaded him to return to Afghanistan. Mihdhar complained about life in the United States. He met with KSM, who remained annoyed at his decision to go AWOL. But KSM's desire to drop him from the operation yielded to Bin Ladin's insistence to keep him.117

By late 2000, Mihdhar was in Mecca, staying with a cousin until February 2001, when he went home to visit his family before returning to Afghanistan. In June 2001, Mihdhar returned once more to Mecca to stay with his cousin for another month. Mihdhar said that Bin Ladin was planning five attacks on the United States. Before leaving, Mihdhar asked his cousin to watch over his home and family because of a job he had to do.118

On July 4, 2001, Mihdhar left Saudi Arabia to return to the United States, arriving at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. Mihdhar gave hijackers his intended address as the Marriott Hotel, New York City, but instead spent one night at another New York hotel. He then joined the group of hijackers in Paterson, reuniting with Nawaf al Hazmi after more than a year. With two months remaining, all 19 hijackers were in the United States and ready to take the final steps toward carrying out the attacks.119

American Airlines Flight 11

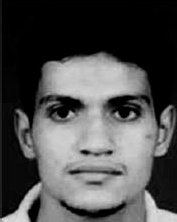

(Left to right)

Mohamed Atta, pilot

Waleed al Shehri

Wail al Shehri

Satam al Suqami

Abdulaziz al Omari

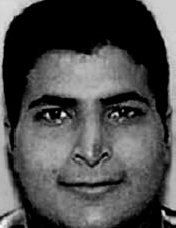

United Airlines Flight 175

(Left to right)

Marwan al Shehhi, pilot

Fayez Banihammad

Ahmed al Ghamdi

Hamza al Ghamdi

Mohand al Shehri

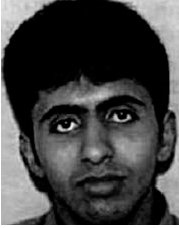

American Airlines Flight 77

(Left to right)

Hani Hanjour, pilot

Nawaf al Hazmi

Khalid al Mihdhar

Majed Moqed

Salem al Hazmi

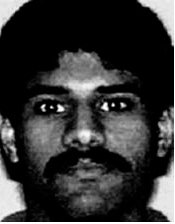

United Airlines Flight 93

(Left to right)

Ziad Jarrah, pilot

Saeed al Ghamdi

Ahmad al Haznawi

Ahmed al Nami

Assistance from Hezbollah and Iran to al Qaeda

As we mentioned in chapter 2, while in Sudan, senior managers in al Qaeda maintained contacts with Iran and the Iranian-supported worldwide terrorist organization Hezbollah, which is based mainly in southern Lebanon and Beirut. Al Qaeda members received advice and training from Hezbollah.

Intelligence indicates the persistence of contacts between Iranian security officials and senior al Qaeda figures after Bin Ladin's return to Afghanistan. Khallad has said that Iran made a concerted effort to strengthen relations with al Qaeda after the October 2000 attack on the USS Cole, but was rebuffed because Bin Ladin did not want to alienate his supporters in Saudi Arabia. Khallad and other detainees have described the willingness of Iranian officials to facilitate the travel of al Qaeda members through Iran, on their way to and from Afghanistan. For example, Iranian border inspectors would be told not to place telltale stamps in the passports of these travelers. Such arrangements were particularly beneficial to Saudi members of al Qaeda.120

Our knowledge of the international travels of the al Qaeda operatives selected for the 9/11 operation remains fragmentary. But we now have evidence suggesting that 8 to 10 of the 14 Saudi "muscle" operatives traveled into or out of Iran between October 2000 and February 2001.121

In October 2000, a senior operative of Hezbollah visited Saudi Arabia to coordinate activities there. He also planned to assist individuals in Saudi Arabia in traveling to Iran during November. A top Hezbollah commander and Saudi Hezbollah contacts were involved.122

Also in October 2000, two future muscle hijackers, Mohand al Shehri and Hamza al Ghamdi, flew from Iran to Kuwait. In November, Ahmed al Ghamdi apparently flew to Beirut, traveling--perhaps by coincidence--on the same flight as a senior Hezbollah operative. Also in November, Salem al Hazmi apparently flew from Saudi Arabia to Beirut.123

In mid-November, we believe, three of the future muscle hijackers, Wail al Shehri, Waleed al Shehri, and Ahmed al Nami, all of whom had obtained their

U.S. visas in late October, traveled in a group from Saudi Arabia to Beirut and then onward to Iran. An associate of a senior Hezbollah operative was on the same flight that took the future hijackers to Iran. Hezbollah officials in Beirut and Iran were expecting the arrival of a group during the same time period. The travel of this group was important enough to merit the attention of senior figures in Hezbollah.124

Later in November, two future muscle hijackers, Satam al Suqami and Majed Moqed, flew into Iran from Bahrain. In February 2001, Khalid al Mihdhar may have taken a flight from Syria to Iran, and then traveled further within Iran to a point near the Afghan border.125

KSM and Binalshibh have confirmed that several of the 9/11 hijackers (at least eight, according to Binalshibh) transited Iran on their way to or from Afghanistan, taking advantage of the Iranian practice of not stamping Saudi passports. They deny any other reason for the hijackers' travel to Iran. They also deny any relationship between the hijackers and Hezbollah.126

In sum, there is strong evidence that Iran facilitated the transit of al Qaeda members into and out of Afghanistan before 9/11, and that some of these were future 9/11 hijackers. There also is circumstantial evidence that senior Hezbollah operatives were closely tracking the travel of some of these future muscle hijackers into Iran in November 2000. However, we cannot rule out the possibility of a remarkable coincidence--that is, that Hezbollah was actually focusing on some other group of individuals traveling from Saudi Arabia during this same time frame, rather than the future hijackers.127

We have found no evidence that Iran or Hezbollah was aware of the planning for what later became the 9/11 attack. At the time of their travel through Iran, the al Qaeda operatives themselves were probably not aware of the specific details of their future operation.

After 9/11, Iran and Hezbollah wished to conceal any past evidence of cooperation with Sunni terrorists associated with al Qaeda. A senior Hezbollah official disclaimed any Hezbollah involvement in 9/11.128

We believe this topic requires further investigation by the U.S. government.