AL QAEDA AIMS AT THE AMERICAN HOMELAND

5.1 Terrorist Entrepreneurs5.2 The "Planes Operation"

5.3 The Hamburg Contingent

5.4 A Money Trail?

5.1 TERRORIST ENTREPRENEURS

By early 1999, al Qaeda was already a potent adversary of the United States. Bin Ladin and his chief of operations, Abu Hafs al Masri, also known as Mohammed Atef, occupied undisputed leadership positions atop al Qaeda's organizational structure. Within this structure, al Qaeda's worldwide terrorist operations relied heavily on the ideas and work of enterprising and strong-willed field commanders who enjoyed considerable autonomy. To understand how the organization actually worked and to introduce the origins of the 9/11 plot, we briefly examine three of these subordinate commanders: Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM), Riduan Isamuddin (better known as Hambali), and Abd al Rahim al Nashiri. We will devote the most attention to Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the chief manager of the "planes operation."

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed

No one exemplifies the model of the terrorist entrepreneur more clearly than Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the principal architect of the 9/11 attacks. KSM followed a rather tortuous path to his eventual membership in al Qaeda.1 Highly educated and equally comfortable in a government office or a terrorist safehouse, KSM applied his imagination, technical aptitude, and managerial skills to hatching and planning an extraordinary array of terrorist schemes. These ideas included conventional car bombing, political assassination, aircraft bombing, hijacking, reservoir poisoning, and, ultimately, the use of aircraft as missiles guided by suicide operatives.

Like his nephew Ramzi Yousef (three years KSM's junior), KSM grew up in Kuwait but traces his ethnic lineage to the Baluchistan region straddling Iran and Pakistan. Raised in a religious family, KSM claims to have joined the Muslim Brotherhood at age 16 and to have become enamored of violent jihad at youth camps in the desert. In 1983, following his graduation from secondary school, KSM left Kuwait to enroll at Chowan College, a small Baptist school in Murfreesboro, North Carolina. After a semester at Chowan, KSM transferred to North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University in Greensboro, which he attended with Yousef's brother, another future al Qaeda member. KSM earned a degree in mechanical engineering in December 1986.3

Detainee Interrogation Reports

Chapters 5 and 7 rely heavily on information obtained from captured al Qaeda members. A number of these "detainees" have firsthand knowledge of the 9/11 plot.

Assessing the truth of statements by these witnesses--sworn enemies of the United States--is challenging. Our access to them has been limited to the review of intelligence reports based on communications received from the locations where the actual interrogations take place. We submitted questions for use in the interrogations, but had no control over whether, when, or how questions of particular interest would be asked. Nor were we allowed to talk to the interrogators so that we could better judge the credibility of the detainees and clarify ambiguities in the reporting. We were told that our requests might disrupt the sensitive interrogation process.

We have nonetheless decided to include information from captured 9/11 conspirators and al Qaeda members in our report. We have evaluated their statements carefully and have attempted to corroborate them with documents and statements of others. In this report, we indicate where such statements provide the foundation for our narrative. We have been authorized to identify by name only ten detainees whose custody has been confirmed officially by the U.S. government.2

Although he apparently did not attract attention for extreme Islamist beliefs or activities while in the United States, KSM plunged into the anti-Soviet Afghan jihad soon after graduating from college. Visiting Pakistan for the first time in early 1987, he traveled to Peshawar, where his brother Zahid introduced him to the famous Afghan mujahid Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, head of the Hizbul-Ittihad El-Islami (Islamic Union Party). Sayyaf became KSM's mentor and provided KSM with military training at Sayyaf's Sada camp. KSM claims he then fought the Soviets and remained at the front for three months before being summoned to perform administrative duties for Abdullah Azzam. KSM next took a job working for an electronics firm that catered to the communications needs of Afghan groups, where he learned about drills used to excavate caves in Afghanistan.4

Between 1988 and 1992, KSM helped run a nongovernmental organization (NGO) in Peshawar and Jalalabad; sponsored by Sayyaf, it was designed to aid young Afghan mujahideen. In 1992, KSM spent some time fighting alongside the mujahideen in Bosnia and supporting that effort with financial donations. After returning briefly to Pakistan, he moved his family to Qatar at the suggestion of the former minister of Islamic affairs of Qatar, Sheikh Abdallah bin Khalid bin Hamad al Thani. KSM took a position in Qatar as project engineer with the Qatari Ministry of Electricity and Water. Although he engaged in extensive international travel during his tenure at the ministry--much of it in furtherance of terrorist activity--KSM would hold his position there until early 1996, when he fled to Pakistan to avoid capture by U.S. authorities.5

KSM first came to the attention of U.S. law enforcement as a result of his cameo role in the first World Trade Center bombing. According to KSM, he learned of Ramzi Yousef's intention to launch an attack inside the United States in 1991 or 1992, when Yousef was receiving explosives training in Afghanistan. During the fall of 1992, while Yousef was building the bomb he would use in that attack, KSM and Yousef had numerous telephone conversations during which Yousef discussed his progress and sought additional funding. On November 3, 1992, KSM wired $660 from Qatar to the bank account of Yousef's co-conspirator, Mohammed Salameh. KSM does not appear to have contributed any more substantially to this operation.6

Yousef's instant notoriety as the mastermind of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing inspired KSM to become involved in planning attacks against the United States. By his own account, KSM's animus toward the United States stemmed not from his experiences there as a student, but rather from his violent disagreement with U.S. foreign policy favoring Israel. In 1994, KSM accompanied Yousef to the Philippines, and the two of them began planning what is now known as the Manila air or "Bojinka" plot--the intended bombing of 12 U.S. commercial jumbo jets over the Pacific during a two-day span. This marked the first time KSM took part in the actual planning of a terrorist operation. While sharing an apartment in Manila during the summer of 1994, he and Yousef acquired chemicals and other materials necessary to construct bombs and timers. They also cased target flights to Hong Kong and Seoul that would have onward legs to the United States. During this same period, KSM and Yousef also developed plans to assassinate President Clinton during his November 1994 trip to Manila, and to bomb U.S.-bound cargo carriers by smuggling jackets containing nitrocellulose on board.7

KSM left the Philippines in September 1994 and met up with Yousef in Karachi following their casing flights. There they enlisted Wali Khan Amin Shah, also known as Usama Asmurai, in the Manila air plot. During the fall of 1994, Yousef returned to Manila and successfully tested the digital watch timer he had invented, bombing a movie theater and a Philippine Airlines flight en route to Tokyo. The plot unraveled after the Philippine authorities discovered Yousef's bomb-making operation in Manila; but by that time, KSM was safely back at his government job in Qatar. Yousef attempted to follow through on the cargo carriers plan, but he was arrested in Islamabad by Pakistani authorities on February 7, 1995, after an accomplice turned him in.8

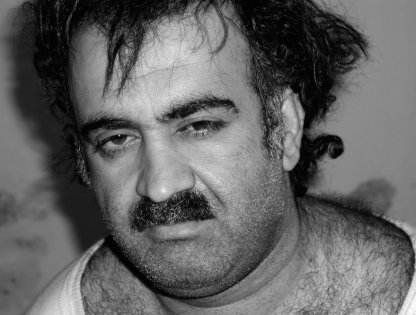

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, mastermind of the 9/11 plot, at the time of his capture in 2003

KSM continued to travel among the worldwide jihadist community after Yousef's arrest, visiting the Sudan, Yemen, Malaysia, and Brazil in 1995. No clear evidence connects him to terrorist activities in those locations. While in Sudan, he reportedly failed in his attempt to meet with Bin Ladin. But KSM did see Atef, who gave him a contact in Brazil. In January 1996, well aware that U.S. authorities were chasing him, he left Qatar for good and fled to Afghanistan, where he renewed his relationship with Rasul Sayyaf.9

Just as KSM was reestablishing himself in Afghanistan in mid-1996, Bin Ladin and his colleagues were also completing their migration from Sudan. Through Atef, KSM arranged a meeting with Bin Ladin in Tora Bora, a mountainous redoubt from the Afghan war days. At the meeting, KSM presented the al Qaeda leader with a menu of ideas for terrorist operations. According to KSM, this meeting was the first time he had seen Bin Ladin since 1989. Although they had fought together in 1987, Bin Ladin and KSM did not yet enjoy an especially close working relationship. Indeed, KSM has acknowledged that Bin Ladin likely agreed to meet with him because of the renown of his nephew, Yousef.10

At the meeting, KSM briefed Bin Ladin and Atef on the first World Trade Center bombing, the Manila air plot, the cargo carriers plan, and other activities pursued by KSM and his colleagues in the Philippines. KSM also presented a proposal for an operation that would involve training pilots who would crash planes into buildings in the United States. This proposal eventually would become the 9/11 operation.11

KSM knew that the successful staging of such an attack would require personnel, money, and logistical support that only an extensive and well-funded organization like al Qaeda could provide. He thought the operation might appeal to Bin Ladin, who had a long record of denouncing the United States.12

From KSM's perspective, Bin Ladin was in the process of consolidating his new position in Afghanistan while hearing out others' ideas, and had not yet settled on an agenda for future anti-U.S. operations. At the meeting, Bin Ladin listened to KSM's ideas without much comment, but did ask KSM formally to join al Qaeda and move his family to Afghanistan.13

KSM declined. He preferred to remain independent and retain the option of working with other mujahideen groups still operating in Afghanistan, including the group led by his old mentor, Sayyaf. Sayyaf was close to Ahmed Shah Massoud, the leader of the Northern Alliance. Therefore working with him might be a problem for KSM because Bin Ladin was building ties to the rival Taliban.

After meeting with Bin Ladin, KSM says he journeyed onward to India, Indonesia, and Malaysia, where he met with Jemaah Islamiah's Hambali. Hambali was an Indonesian veteran of the Afghan war looking to expand the jihad into Southeast Asia. In Iran, KSM rejoined his family and arranged to move them to Karachi; he claims to have relocated by January 1997.14

After settling his family in Karachi, KSM tried to join the mujahid leader Ibn al Khattab in Chechnya. Unable to travel through Azerbaijan, KSM returned to Karachi and then to Afghanistan to renew contacts with Bin Ladin and his colleagues. Though KSM may not have been a member of al Qaeda at this time, he admits traveling frequently between Pakistan and Afghanistan in 1997 and the first half of 1998, visiting Bin Ladin and cultivating relationships with his lieutenants, Atef and Sayf al Adl, by assisting them with computer and media projects.15

According to KSM, the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Nairobi and Dar es Salaam marked a watershed in the evolution of the 9/11 plot. KSM claims these bombings convinced him that Bin Ladin was truly committed to attacking the United States. He continued to make himself useful, collecting news articles and helping other al Qaeda members with their outdated computer equipment. Bin Ladin, apparently at Atef's urging, finally decided to give KSM the green light for the 9/11 operation sometime in late 1998 or early 1999.16

KSM then accepted Bin Ladin's standing invitation to move to Kandahar and work directly with al Qaeda. In addition to supervising the planning and preparations for the 9/11 operation, KSM worked with and eventually led al Qaeda's media committee. But KSM states he refused to swear a formal oath of allegiance to Bin Ladin, thereby retaining a last vestige of his cherished autonomy.17

At this point, late 1998 to early 1999, planning for the 9/11 operation began in earnest. Yet while the 9/11 project occupied the bulk of KSM's attention, he continued to consider other possibilities for terrorist attacks. For example, he sent al Qaeda operative Issa al Britani to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, to learn about the jihad in Southeast Asia from Hambali. Thereafter, KSM claims, at Bin Ladin's direction in early 2001, he sent Britani to the United States to case potential economic and "Jewish" targets in New York City. Furthermore, during the summer of 2001, KSM approached Bin Ladin with the idea of recruiting a Saudi Arabian air force pilot to commandeer a Saudi fighter jet and attack the Israeli city of Eilat. Bin Ladin reportedly liked this proposal, but he instructed KSM to concentrate on the 9/11 operation first. Similarly, KSM's proposals to Atef around this same time for attacks in Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, and the Maldives were never executed, although Hambali's Jemaah Islamiah operatives did some casing of possible targets.18

KSM appears to have been popular among the al Qaeda rank and file. He was reportedly regarded as an effective leader, especially after the 9/11 attacks. Coworkers describe him as an intelligent, efficient, and even-tempered manager who approached his projects with a single-minded dedication that he expected his colleagues to share. Al Qaeda associate Abu Zubaydah has expressed more qualified admiration for KSM's innate creativity, emphasizing instead his ability to incorporate the improvements suggested by others. Nashiri has been similarly measured, observing that although KSM floated many general ideas for attacks, he rarely conceived a specific operation himself.19 Perhaps these estimates reflect a touch of jealousy; in any case, KSM was plainly a capable coordinator, having had years to hone his skills and build relationships.

Hambali

Al Qaeda's success in fostering terrorism in Southeast Asia stems largely from its close relationship with Jemaah Islamiah (JI). In that relationship, Hambali became the key coordinator. Born and educated in Indonesia, Hambali moved to Malaysia in the early 1980s to find work. There he claims to have become a follower of the Islamist extremist teachings of various clerics, including one named Abdullah Sungkar. Sungkar first inspired Hambali to share the vision of establishing a radical Islamist regime in Southeast Asia, then furthered Hambali's instruction in jihad by sending him to Afghanistan in 1986.After undergoing training at Rasul Sayyaf's Sada camp (where KSM would later train), Hambali fought against the Soviets; he eventually returned to Malaysia after 18 months in Afghanistan. By 1998, Hambali would assume responsibility for the Malaysia/Singapore region within Sungkar's newly formed terrorist organization, the JI.20

Also by 1998, Sungkar and JI spiritual leader Abu Bakar Bashir had accepted Bin Ladin's offer to ally JI with al Qaeda in waging war against Christians and Jews.21 Hambali met with KSM in Karachi to arrange for JI members to receive training in Afghanistan at al Qaeda's camps. In addition to his close working relationship with KSM, Hambali soon began dealing with Atef as well. Al Qaeda began funding JI's increasingly ambitious terrorist plans, which Atef and KSM sought to expand. Under this arrangement, JI would perform the necessary casing activities and locate bomb-making materials and other supplies. Al Qaeda would underwrite operations, provide bomb-making expertise, and deliver suicide operatives.22

The al Qaeda-JI partnership yielded a number of proposals that would marry al Qaeda's financial and technical strengths with JI's access to materials and local operatives. Here, Hambali played the critical role of coordinator, as he distributed al Qaeda funds earmarked for the joint operations. In one especially notable example, Atef turned to Hambali when al Qaeda needed a scientist to take over its biological weapons program. Hambali obliged by introducing a U.S.-educated JI member, Yazid Sufaat, to Ayman al Zawahiri in Kandahar. In 2001, Sufaat would spend several months attempting to cultivate anthrax for al Qaeda in a laboratory he helped set up near the Kandahar airport.23

Hambali did not originally orient JI's operations toward attacking the United States, but his involvement with al Qaeda appears to have inspired him to pursue American targets. KSM, in his post-capture interrogations, has taken credit for this shift, claiming to have urged the JI operations chief to concentrate on attacks designed to hurt the U.S. economy.24 Hambali's newfound interest in striking against the United States manifested itself in a spate of terrorist plans. Fortunately, none came to fruition.

In addition to staging actual terrorist attacks in partnership with al Qaeda, Hambali and JI assisted al Qaeda operatives passing through Kuala Lumpur. One important occasion was in December 1999-January 2000. Hambali accommodated KSM's requests to help several veterans whom KSM had just finished training in Karachi. They included Tawfiq bin Attash, also known as Khallad, who later would help bomb the USS Cole, and future 9/11 hijackers Nawaf al Hazmi and Khalid al Mihdhar. Hambali arranged lodging for them and helped them purchase airline tickets for their onward travel. Later that year, Hambali and his crew would provide accommodations and other assistance (including information on flight schools and help in acquiring ammonium nitrate) for Zacarias Moussaoui, an al Qaeda operative sent to Malaysia by Atef and KSM.25

Hambali used Bin Ladin's Afghan facilities as a training ground for JI recruits. Though he had a close relationship with Atef and KSM, he maintained JI's institutional independence from al Qaeda. Hambali insists that he did not discuss operations with Bin Ladin or swear allegiance to him, having already given such a pledge of loyalty to Bashir, Sungkar's successor as JI leader. Thus, like any powerful bureaucrat defending his domain, Hambali objected when al Qaeda leadership tried to assign JI members to terrorist projects without notifying him.26

Abd al Rahim al Nashiri

KSM and Hambali both decided to join forces with al Qaeda because their terrorist aspirations required the money and manpower that only a robust organization like al Qaeda could supply. On the other hand, Abd al Rahim al Nashiri--the mastermind of the Cole bombing and the eventual head of al Qaeda operations in the Arabian Peninsula--appears to have originally been recruited to his career as a terrorist by Bin Ladin himself.

Having already participated in the Afghan jihad, Nashiri accompanied a group of some 30 mujahideen in pursuit of jihad in Tajikistan in 1996.When serious fighting failed to materialize, the group traveled to Jalalabad and encountered Bin Ladin, who had recently returned from Sudan. Bin Ladin addressed them at length, urging the group to join him in a "jihad against the Americans." Although all were urged to swear loyalty to Bin Ladin, many, including Nashiri, found the notion distasteful and refused. After several days of indoctrination that included a barrage of news clippings and television documentaries, Nashiri left Afghanistan, first returning to his native Saudi Arabia and then visiting his home in Yemen. There, he says, the idea for his first terrorist operation took shape as he noticed many U.S. and other foreign ships plying the waters along the southwest coast of Yemen.27

Nashiri returned to Afghanistan, probably in 1997, primarily to check on relatives fighting there and also to learn about the Taliban. He again encountered Bin Ladin, still recruiting for "the coming battle with the United States." Nashiri pursued a more conventional military jihad, joining the Taliban forces in their fight against Ahmed Massoud's Northern Alliance and shuttling back and forth between the front and Kandahar, where he would see Bin Ladin and meet with other mujahideen. During this period, Nashiri also led a plot to smuggle four Russian-made antitank missiles into Saudi Arabia from Yemen in early 1998 and helped an embassy bombing operative obtain a Yemeni passport.28

At some point, Nashiri joined al Qaeda. His cousin, Jihad Mohammad Ali al Makki, also known as Azzam, was a suicide bomber for the Nairobi attack. Nashiri traveled between Yemen and Afghanistan. In late 1998, Nashiri proposed mounting an attack against a U.S. vessel. Bin Ladin approved. He directed Nashiri to start the planning and send operatives to Yemen, and he later provided money.29

Nashiri reported directly to Bin Ladin, the only other person who, according to Nashiri, knew all the details of the operation. When Nashiri had difficulty finding U.S. naval vessels to attack along the western coast of Yemen, Bin Ladin reportedly instructed him to case the Port of Aden, on the southern coast, instead.30 The eventual result was an attempted attack on the USS The Sullivans in January 2000 and the successful attack, in October 2000, on the USS Cole.

Nashiri's success brought him instant status within al Qaeda. He later was recognized as the chief of al Qaeda operations in and around the Arabian Peninsula. While Nashiri continued to consult Bin Ladin on the planning of subsequent terrorist projects, he retained discretion in selecting operatives and devising attacks. In the two years between the Cole bombing and Nashiri's capture, he would supervise several more proposed operations for al Qaeda. The October 6, 2002, bombing of the French tanker Limburg in the Gulf of Aden also was Nashiri's handiwork. Although Bin Ladin urged Nashiri to continue plotting strikes against U.S. interests in the Persian Gulf, Nashiri maintains that he actually delayed one of these projects because of security concerns.31 Those concerns, it seems, were well placed, as Nashiri's November 2002 capture in the United Arab Emirates finally ended his career as a terrorist.