HEROISM AND HORROR

9.1 Preparedness as of September 119.2 September 11, 2001

9.3 Emergency Response at the Pentagon

9.4 Analysis

9.1 PREPAREDNESS AS OF SEPTEMBER 11

Emergency response is a product of preparedness. On the morning of September 11, 2001, the last best hope for the community of people working in or visiting the World Trade Center rested not with national policymakers but with private firms and local public servants, especially the first responders: fire, police, emergency medical service, and building safety professionals.

Building Preparedness The World Trade Center.The World Trade Center (WTC) complex was built for the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Construction began in 1966, and tenants began to occupy its space in 1970.The Twin Towers came to occupy a unique and symbolic place in the culture of New York City and America.

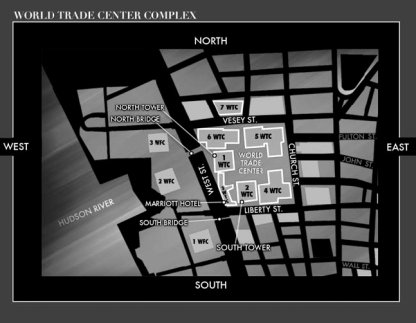

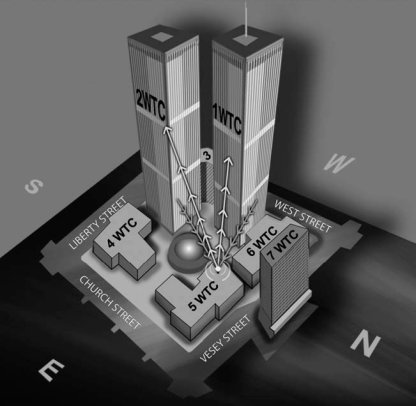

The WTC actually consisted of seven buildings, including one hotel, spread across 16 acres of land. The buildings were connected by an underground mall (the concourse).The Twin Towers (1 WTC, or the North Tower, and 2 WTC, or the South Tower) were the signature structures, containing 10.4 million square feet of office space. Both towers had 110 stories, were about 1, 350 feet high, and were square; each wall measured 208 feet in length. On any given workday, up to 50, 000 office workers occupied the towers, and 40, 000 people passed through the complex.1

Each tower contained three central stairwells, which ran essentially from top to bottom, and 99 elevators. Generally, elevators originating in the lobby ran to "sky lobbies" on higher floors, where additional elevators carried passengers to the tops of the buildings.2

Stairwells A and C ran from the 110th floor to the raised mezzanine level of the lobby. Stairwell B ran from the 107th floor to level B6, six floors below ground, and was accessible from the West Street lobby level, which was one

floor below the mezzanine. All three stairwells ran essentially straight up and down, except for two deviations in stairwells A and C where the staircase jutted out toward the perimeter of the building. On the upper and lower boundaries of these deviations were transfer hallways contained within the stairwell proper. Each hallway contained smoke doors to prevent smoke from rising from lower to upper portions of the building; they were kept closed but not locked. Doors leading from tenant space into the stairwells were never kept locked; reentry from the stairwells was generally possible on at least every fourth floor.3

Doors leading to the roof were locked. There was no rooftop evacuation plan. The roofs of both the North Tower and the South Tower were sloped and cluttered surfaces with radiation hazards, making them impractical for helicopter landings and as staging areas for civilians. Although the South Tower roof had a helipad, it did not meet 1994 Federal Aviation Administration guidelines.4

The 1993 Terrorist Bombing of the WTC and the Port Authority's Response.Unlike most of America, New York City and specifically the World

Trade Center had been the target of terrorist attacks before 9/11.At 12:18 P.M. on February 26, 1993, a 1, 500-pound bomb stashed in a rental van was detonated on a parking garage ramp beneath the Twin Towers. The explosion killed six people, injured about 1, 000 more, and exposed vulnerabilities in the World Trade Center's and the city's emergency preparedness.5

The towers lost power and communications capability. Generators had to be shut down to ensure safety, and elevators stopped. The public-address system and emergency lighting systems failed. The unlit stairwells filled with smoke and were so dark as to be impassable. Rescue efforts by the Fire Department of New York (FDNY) were hampered by the inability of its radios to function in buildings as large as the Twin Towers. The 911 emergency call system was overwhelmed. The general evacuation of the towers' occupants via the stairwells took more than four hours.6

Several small groups of people who were physically unable to descend the stairs were evacuated from the roof of the South Tower by New York Police Department (NYPD) helicopters. At least one person was lifted from the North Tower roof by the NYPD in a dangerous helicopter rappel operation-- 15 hours after the bombing. General knowledge that these air rescues had occurred appears to have left a number of civilians who worked in the Twin Towers with the false impression that helicopter rescues were part of the WTC evacuation plan and that rescue from the roof was a viable, if not favored, option for those who worked on upper floors. Although they were considered after 1993, helicopter evacuations in fact were not incorporated into the WTC fire safety plan.7

To address the problems encountered during the response to the 1993 bombing, the Port Authority spent an initial $100 million to make physical, structural, and technological improvements to the WTC, as well as to enhance its fire safety plan and reorganize and bolster its fire safety and security staffs.8

Substantial enhancements were made to power sources and exits. Fluorescent signs and markings were added in and near stairwells. The Port Authority also installed a sophisticated computerized fire alarm system with redundant electronics and control panels, and state-of-the-art fire command stations were placed in the lobby of each tower.9

To manage fire emergency preparedness and operations, the Port Authority created the dedicated position of fire safety director. The director supervised a team of deputy fire safety directors, one of whom was on duty at the fire command station in the lobby of each tower at all times. He or she would be responsible for communicating with building occupants during an emergency.10

The Port Authority also sought to prepare civilians better for future emergencies. Deputy fire safety directors conducted fire drills at least twice a year, with advance notice to tenants. "Fire safety teams" were selected from among civilian employees on each floor and consisted of a fire warden, deputy fire wardens, and searchers. The standard procedure for fire drills was for fire wardens to lead co-workers in their respective areas to the center of the floor, where they would use the emergency intercom phone to obtain specific information on how to proceed. Some civilians have told us that their evacuation on September 11 was greatly aided by changes and training implemented by the Port Authority in response to the 1993 bombing.11

But during these drills, civilians were not directed into the stairwells, or provided with information about their configuration and about the existence of transfer hallways and smoke doors. Neither full nor partial evacuation drills were held. Moreover, participation in drills that were held varied greatly from tenant to tenant. In general, civilians were never told not to evacuate up. The standard fire drill announcement advised participants that in the event of an actual emergency, they would be directed to descend to at least three floors below the fire. Most civilians recall simply being taught to await the instructions that would be provided at the time of an emergency. Civilians were not informed that rooftop evacuations were not part of the evacuation plan, or that doors to the roof were kept locked. The Port Authority acknowledges that it had no protocol for rescuing people trapped above a fire in the towers.12

Six weeks before the September 11 attacks, control of the WTC was transferred by net lease to a private developer, Silverstein Properties. Select Port Authority employees were designated to assist with the transition. Others remained on-site but were no longer part of the official chain of command. However, on September 11, most Port Authority World Trade Department employees--including those not on the designated "transition team"-- reported to their regular stations to provide assistance throughout the morning. Although Silverstein Properties was in charge of the WTC on September 11, the WTC fire safety plan remained essentially the same.13

Preparedness of First Responders

On 9/11, the principal first responders were from the Fire Department of New York, the New York Police Department, the Port Authority Police Department (PAPD), and the Mayor's Office of Emergency Management (OEM).

Port Authority Police Department.On September 11, 2001, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Police Department consisted of 1, 331 officers, many of whom were trained in fire suppression methods as well as in law enforcement. The PAPD was led by a superintendent. There was a separate PAPD command for each of the Port Authority's nine facilities, including the World Trade Center.14

Most Port Authority police commands used ultra-high-frequency radios. Although all the radios were capable of using more than one channel, most PAPD officers used one local channel. The local channels were low-wattage and worked only in the immediate vicinity of that command. The PAPD also had an agencywide channel, but not all commands could access it.15

As of September 11, the Port Authority lacked any standard operating procedures to govern how officers from multiple commands would respond to and then be staged and utilized at a major incident at the WTC. In particular, there were no standard operating procedures covering how different commands should communicate via radio during such an incident.

The New York Police Department.The 40, 000-officer NYPD was headed by a police commissioner, whose duties were not primarily operational but who retained operational authority. Much of the NYPD's operational activities were run by the chief of department. In the event of a major emergency, a leading role would be played by the Special Operations Division. This division included the Aviation Unit, which provided helicopters for surveys and rescues, and the Emergency Service Unit (ESU), which carried out specialized rescue missions. The NYPD had specific and detailed standard operating procedures for the dispatch of officers to an incident, depending on the incident's magnitude.16

The NYPD precincts were divided into 35 different radio zones, with a central radio dispatcher assigned to each. In addition, there were several radio channels for citywide operations. Officers had portable radios with 20 or more available channels, so that the user could respond outside his or her precinct. ESU teams also had these channels but at an operation would use a separate point-to-point channel (which was not monitored by a dispatcher).17

The NYPD also supervised the city's 911 emergency call system. Its approximately 1, 200 operators, radio dispatchers, and supervisors were civilian employees of the NYPD. They were trained in the rudiments of emergency response. When a 911 call concerned a fire, it was transferred to FDNY dispatch.18

The Fire Department of New York.The 11, 000-member FDNY was headed by a fire commissioner who, unlike the police commissioner, lacked operational authority. Operations were headed by the chief of department-- the sole five-star chief.19

The FDNY was organized in nine separate geographic divisions. Each division was further divided into between four to seven battalions. Each battalion contained typically between three and four engine companies and two to four ladder companies. In total, the FDNY had 205 engine companies and 133 ladder companies. On-duty ladder companies consisted of a captain or lieutenant and five firefighters; on-duty engine companies consisted of a captain or lieutenant and normally four firefighters. Ladder companies' primary function was to conduct rescues; engine companies focused on extinguishing fires.20

The FDNY's Specialized Operations Command (SOC) contained a limited number of units that were of particular importance in responding to a terrorist attack or other major incident. The department's five rescue companies and seven squad companies performed specialized and highly risky rescue operations.21

The logistics of fire operations were directed by Fire Dispatch Operations Division, which had a center in each of the five boroughs. All 911 calls concerning fire emergencies were transferred to FDNY dispatch.22

As of September 11, FDNY companies and chiefs responding to a fire used analog, point-to-point radios that had six normal operating channels. Typically, the companies would operate on the same tactical channel, which chiefs on the scene would monitor and use to communicate with the firefighters. Chiefs at a fire operation also would use a separate command channel. Because these point-to-point radios had weak signal strength, communications on them could be heard only by other FDNY personnel in the immediate vicinity. In addition, the FDNY had a dispatch frequency for each of the five boroughs; these were not point-to-point channels and could be monitored from around the city.23

The FDNY's radios performed poorly during the 1993 WTC bombing for two reasons. First, the radios signals often did not succeed in penetrating the numerous steel and concrete floors that separated companies attempting to communicate; and second, so many different companies were attempting to use the same point-to-point channel that communications became unintelligible.24

The Port Authority installed, at its own expense, a repeater system in 1994 to greatly enhance FDNY radio communications in the difficult high-rise environment of the Twin Towers. The Port Authority recommended leaving the repeater system on at all times. The FDNY requested, however, that the repeater be turned on only when it was actually needed because the channel could cause interference with other FDNY operations in Lower Manhattan. The repeater system was installed at the Port Authority police desk in 5 WTC, to be activated by members of the Port Authority police when the FDNY units responding to the WTC complex so requested. However, in the spring of 2000 the FDNY asked that an activation console for the repeater system be placed instead in the lobby fire safety desk of each of the towers, making FDNY personnel entirely responsible for its activation. The Port Authority complied.25

Between 1998 and 2000, fewer people died from fires in New York City than in any three-year period since accurate measurements began in 1946. Firefighter deaths--a total of 22 during the 1990s--compared favorably with the most tranquil periods in the department's history.26

Office of Emergency Management and Interagency Preparedness.

In 1996, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani created the Mayor's Office of Emergency Management, which had three basic functions. First, OEM's Watch Command was to monitor the city's key communications channels--including radio frequencies of FDNY dispatch and the NYPD--and other data. A second purpose of the OEM was to improve New York City's response to major incidents, including terrorist attacks, by planning and conducting exercises and drills that would involve multiple city agencies, particularly the NYPD and FDNY.Third, the OEM would play a crucial role in managing the city's overall response to an incident. After OEM's Emergency Operations Center was activated, designated liaisons from relevant agencies, as well as the mayor and his or her senior staff, would respond there. In addition, an OEM field responder would be sent to the scene to ensure that the response was coordinated.27

The OEM's headquarters was located at 7 WTC. Some questioned locating it both so close to a previous terrorist target and on the 23rd floor of a building (difficult to access should elevators become inoperable). There was no backup site.28

In July 2001, Mayor Giuliani updated a directive titled "Direction and Control of Emergencies in the City of New York." Its purpose was to eliminate "potential conflict among responding agencies which may have areas of overlapping expertise and responsibility." The directive sought to accomplish this objective by designating, for different types of emergencies, an appropriate agency as "Incident Commander." This Incident Commander would be "responsible for the management of the City's response to the emergency," while the OEM was "designated the 'On Scene Interagency Coordinator.'"29

Nevertheless, the FDNY and NYPD each considered itself operationally autonomous. As of September 11, they were not prepared to comprehensively coordinate their efforts in responding to a major incident. The OEM had not overcome this problem.